Out of sight, top of mind

Kaitlyn Landram

Apr 15, 2024

Thirty-two years after smallpox was eradicated, scientists unearthed the virus’s genetic signature from within mummified remains. Four years later, an anthrax outbreak that affected dozens of people and killed thousands of reindeer was linked to thawing permafrost in the Arctic.

“Permafrost is thawing at unprecedented rates in high latitude and altitude regions," said Robyn Barbato, Senior Scientist at CRREL. “Our latest research results show that microorganisms are heterogeneously distributed in permafrost and activate as temperatures rise. Some of these microorganisms have pathogenic features, and the ecological and clinical implications of when and where these pathogens will enter the environment are largely unknown.”

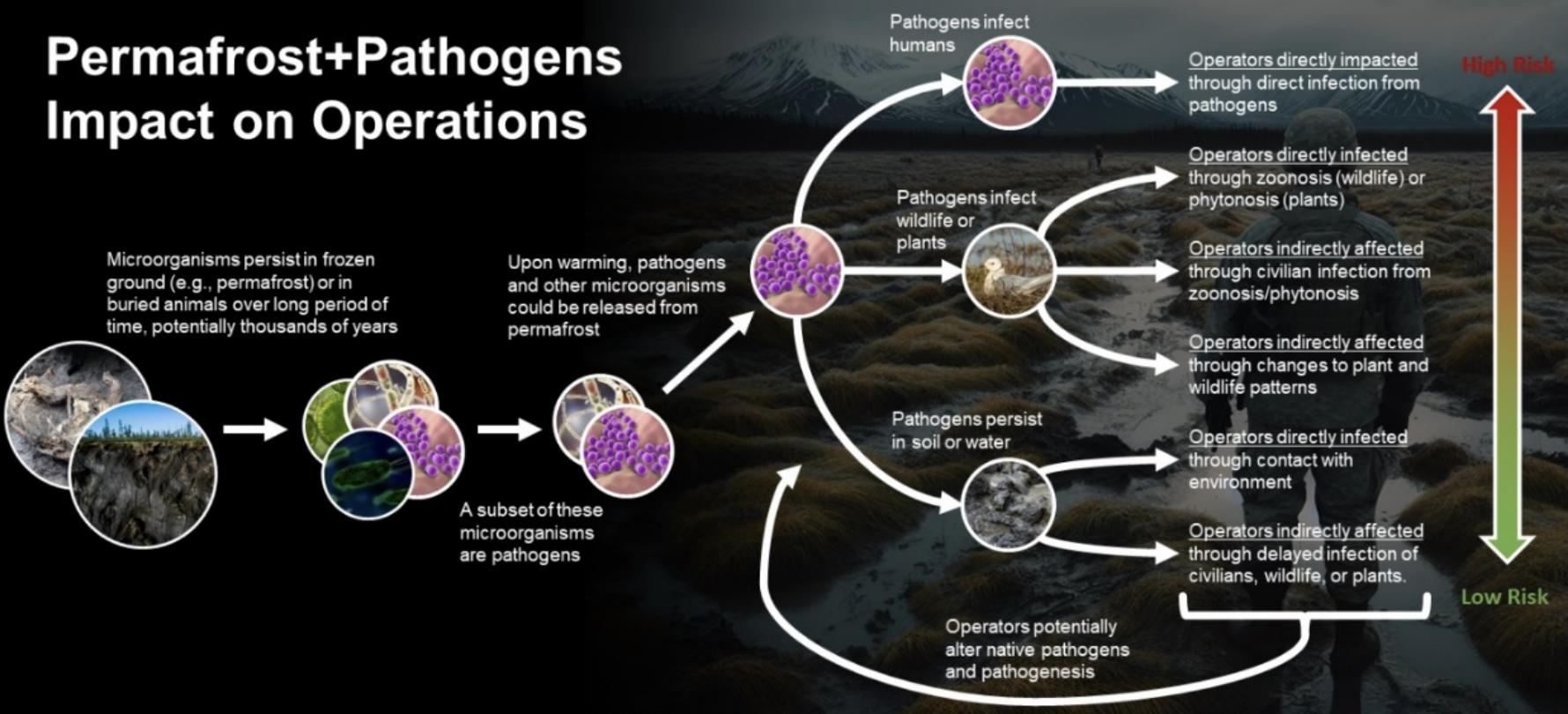

Ultimately, as global temperatures warm, layers of soil that had been frozen for up to 700,000 years are thawing and heightening the risk of a pathogen resurgence that predates modern immunity.

“Our primary concern is that pathogens that have been frozen in the Arctic for thousands of years could thaw and regain their ability to infect humans, animals, or plants,” explained Jill Brandenberger, Advisor Environmental Intelligence at the Pacific Northwest National Lab. “This exposure pathway for pathogens is plausible, but we lack the ability to anticipate what pathogens may be released from the various forms of permafrost.”

To determine just what that risk is, particularly to defense operations in the Arctic, military operators, medical professionals, academic scientists, cold-region scientists, and engineers gathered at a Pathogens and Permafrost Workshop in November 2023. Chris McComb, Associate Professor of Mechanical Engineering, moderated the workshop. Attendees established baseline knowledge to assess implications on human health and develop sustainable operations in the evolving Arctic environment.

“Our job is to provide scientific leadership for the defense and security enterprise so that their operations are more resilient,” said Lilian Alessa, internationally renowned senior defense and security expert who co-directs the Center for Resilient Communities. “Homeland defense entails a much broader set of activities than most people realize and that includes ensuring that people, technology, and the environment work together better. While disease is our primary concern, we are also aware that microbes can restructure ecosystems and, as a result, economies and cultures.”At the end of the day, this is about driving policy to make sure we don’t unknowingly release a world-ending virus … even if the risk of that is small.

Chris McComb, Associate Professor

The working group shared the following recommendations:

- A coordinating authority is needed - Excellent work exists in isolated pockets across USG agencies, academia, and National Labs. A coordinating authority could establish a vital, comprehensive baseline of what we know now, and what information is needed for defense planning today and into the future.

- Planning needs to start now- Accelerating, compounding processes, have the potential to release a significant pulse of viruses, bacteria, and fungi into the environment. Many mitigation strategies can be readily accomplished by requiring coordinated planning both within DOD and across partners.

- We know the first actions to take - The first steps involve aggregating and meta-analysis of existing data and archived samples to guide routine sampling. The outputs of these activities will inform both future science and technology needs in this domain and military planning doctrine.

“Many times the broad set of relatively unknown challenges and activities to address them in an extreme environment like the high latitudes are overlooked and left for the operators to overcome when an event occurs. Thus the infrastructure, operational protocols and personnel are potentially vulnerable and at risk, said Jason Weale, Extreme Cold Weather Engineer & Remote Sensing GIS Subject Matter Expert. “We aim to develop fundamental knowledge and apply what we learn to ensure timely responses supported by resilient infrastructure, safe operations and enduring presence.”

McComb, who uses computational modeling to understand how permafrost affects communities, is hopeful that his team at CMU can use machine learning to better understand the risk from pathogens too.

“When someone’s job puts them around radiation, they wear a badge that measures the exposure. This badge is vital for safety and risk management,” explained McComb. “We may be able to use a similar idea to digitally track the exposure risk to potential pathogens and use that information to ensure global safety. At the end of the day, this is about driving policy to make sure we don’t unknowingly release a world-ending virus … even if the risk of that is small.”

Robyn Barbato, Jill Brandenberger, Lilian Alessa, and Jason Weale were lead organizers of the workshop hosted in November 2023. The next meeting will be held in May 2024.